The series of 28 drypoint print images, (“After Rembrandt’s The Three Crosses” working title), is a project that utilizes the properties of the medium of drypoint to be drawn, printed, re-drawn, altered and printed again. Utilizing one of Rembrandt’s best known prints, Christ Crucified Between Two Thieves: The Three Crosses (1653) as a starting point, the project expands the narrative potential of the original work by creating images of events taking place on the same landscape over time to realign the timelessness of his religiously inspired original with the timeliness of contemporary socio-political struggle in the settler-colonial context of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories. Western art presents itself as God given, timeless and immutable. In contrast, my project advances the potential latent within the work by moving the narrative forward in time through erasure; drawing on top of the original work with diverse imagery which shows the instability of occupation. I began by creating a copper plate of the exact size of Rembrandt’s print through photo-etching. I then drew on top of the plate creating new layers, making ghost-like images of the previous state in the background. The new images propose forgotten or overlooked narratives through a break with historical continuity. The project is driven by the mediums of printmaking and drawing because they provide a unique material manifestation of variation, erasure, and layering as an opportunity to consider the idea of open-endedness and the idea of contingency, that which is fleeting and fragile.

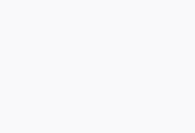

Rembrandt is now celebrated for altering his print images in the process of their creation. He made variations to several of his print images; the largest and best known example being The Three Crosses (plate size 18 x 15.75 inches), which he re-worked in five variations over a period of years around 1653. The different motivations that caused Rembrandt to make changes to The Three Crosses give insight into his working artistic method. One purpose of the variations was simply a way to make corrections or to refine the composition. The most dramatic changes occur to the mood of the scene by adding more contrast between dark and light to increase the sense of drama between the fourth and fifth state. This use of abstraction has been utilized as an example of how the work influenced modern artists. Another reason was to correct inaccuracies in the historical costumes of the large crowd. For example, the Roman soldiers on horseback lose their medieval armor and feathered plumes in exchange for a large “oriental” hat between the third and fourth state. This means that when composing the image, Rembrandt sketched directly onto the plate in a way akin to a preparatory drawing.

One of the consequences of this approach to creating a print image, is that Rembrandt stood out as “experimental” artist among his contemporaries. Robert Fucci’s book Rembrandt’s Changing Impressions, emphasizes the experimental nature of the work and credits him with not only “thematiz[ing] the notion of change” but realizing the potential of printmaking to create multiple variations of the same image as both artistic innovation and to satisfy collectors: “If Rembrandt generated some of the changes in the hope that collectors would purchase multiple impressions, we might consider that they welcomed the occasions to do so. His changes in print offered the opportunity for comparison in a way generally unavailable in other mediums, and invited discussion – then, as now, – about the possibilities of expanding the way an image looked and the meanings it conveyed, in both aesthetic and iconographic terms. …Rembrandt’s conception of printmaking as a flexible medium for the creation of a changing multiple product designed to remain visible to the public in its variations, whether subtle and shimmering, or dramatic and enigmatic, is surely one of the most creative projects ever undertaken in the history of art.” (1) The spontaneity and openness of the working method is surprising, since it contrasts sharply with other artists who wanted to keep their methods secret. For example, the recent “discovery” by David Hockney and others that artists like Vermeer (1632 – 1675) used a camera obscura, changes how we regard the secretive nature of their works. Through displaying his working method, Rembrandt was signaling to his audience that he had nothing to hide.

If the academic tradition of Western art has privileged the hierarchy of art mediums, with painting as the apotheosis, then one of the prevailing values of contemporary art is its open-endedness and potential for re-configuration. While installation and performance hold a special place in this debate, as new mediums that re-configure the boundaries of art making, many authors have also made the case for drawing and printmaking, which have gained their freedom from their previous subordination to painting. By showing erasure as part of the work, Rembrandt’s print connects to what Christian Rattemeyer calls the “radical act” of a contemporary work like Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) which “occupy another order of invention and expression” to that of the “masterpiece”: “Drawings are often produced in series or groups, in spurts and fits, with false starts and unclear endings. We value them for their immediacy, for the insights they offer into the process of the creative act, for their fragmentary, incomplete nature, their intimacy and directness; in drawings we seek truth, not power.” (2)

Without the same baggage as painting, drawing is less encumbered by its own history. The fact that drawing was primarily a medium of practice, trial and error has become it’s redemption. In celebrating drawing over painting, Emma Dexter senses an artistic equivalent to the philosophical movement from Plato to Heidegger, or from the idea of “being” to “becoming”: “Drawing forever describes its own making in its becoming. In a sense, drawing is nothing more than that, and in its eternal incompletion always re-enacts imperfection and incompletion… the act of drawing itself betokens honesty and transparency – all the marks and tracks, whether deliberate or not, are there for all to see in perpetuity. Any erasures or attempts to change the line mid-flow are obvious – drawing is a form that wears its mistakes and errors on its sleeve. Oil painting, by contrast, is an art of accretion and concealment. It is possible to paint an entirely different painting on top of another. Drawing is improvisatory and always in motion, in the sense that it can proceed ad infinitum without closure or completion, continually part of a process that is never-ending.” (3)

Other authors make a similar case about printmaking, whose range of processes are united in the idea of variation and alteration as a hallmark of the mediums. For example, Timothy van Laar contends that “the development of an artwork through long and indirect procedures demands a distinctive manner of thinking. Actions do not have immediate effects; surfaces are built in layers; evaluation and reconsideration are done in a leisurely fashion.” (4) The idea that an artwork can be open-ended and unfinished was a guiding principle of Robert Rauschenberg, who utilized the full possibilities of printmaking as a method of recombination.

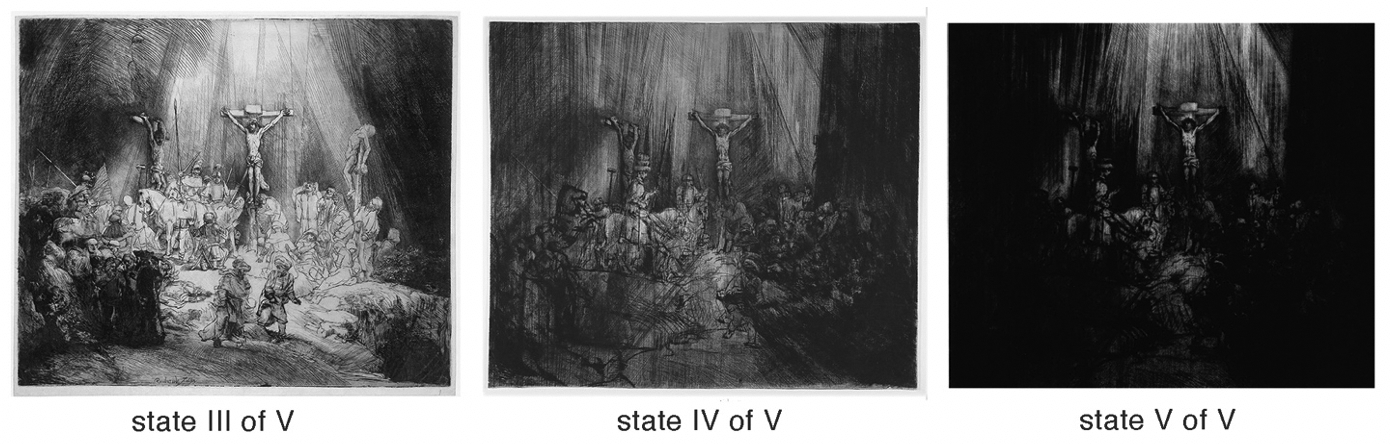

The process of printmaking invites collaboration; often the artist who creates the plate and the artist who print the plate are different. The fact that Rembrandt made the changes to his images and printed them himself was an asset for his method of working as a form of self-collaboration. The flexibility of the medium to create multiples invites what we would today consider a collaborative artwork. Rembrandt had already done this to one of his contemporaries, transforming a Hercules Segers from Tobias and the Angel to The Flight into Egypt. Other artists did the same thing to Rembrandt after his death by appropriating, reprinting and transforming his original plates. For example, William Baillie added a lightning bolt to Rembrandt’s The Three Trees more than a hundred years after it was originally printed.

The artistic potential of such collaborative artmaking expanded in the twentieth century with Dada, exploded with conceptual art and reached a peak in relational aesthetics. The practices privileged a continual de-materialization of the art object, culminating in events, platforms and stages for the art-world that theoretically make art more democratic because they are not about the procession of a valuable thing but result in immaterial experiences open to all. The critique of the hubris of such works, by historians like Claire Bishop has deflated their rhetoric but hasn’t overwhelmed their power.

Printmaking stands at an interesting intersection of the visual arts today precisely because of its in betweenness. Two aspects specific to the medium are worth further consideration because of their reverberations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: the relationship of the plate to the print and the relation of all the prints in the edition, it short, it’s reproduction.

Both the positive and the negative consequences of the technological reproduction of art have been argued; Prints have always been more than one and therefore there is no original, one print; The work is made and exists as a set. Timothy Van Laar claims that the defining feature of the print is the edition, which is the key aspect of the way it functions as an artwork: The edition is a “spatially discontinuous object” that creates an equal but flexible structure that is dispersed and akin to the community of citizens in a democracy, “a unity of equal individuals”. (5) It was Walter Benjamin’s famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility that originally made the argument that the dispersed artwork allowed for a heterogeneous reading and non-standardized reception: “The consideration of the techniques of reproduction, more than any other line of research, clarifies the decisive importance of reception. Thus it become to some degree possible to correct the process of reification which takes place in a work of art. The consideration of mass art leads to a revision of the concept of genius. It reminds us not to give priority to the inspiration, which participates in the becoming of the work of art, over and against the demand which alone allows inspiration to come to fruition.” (6) The openness of context on interpretation has been regarded as a defining feature of the democratic power of reproduction because it takes place beyond the official confines of a ritualistic context.

Because printmaking is the product of commercial reproduction methods, vulgar economy is its inheritance: technological innovations that proceed to make reproductions faster and cheaper. Mass-produced art has obviously been utilized in the service of selling products and experiences within capitalism and is complicit in the proliferation of kitsch culture. With an increasing conglomeration and consolidation of mass art in the hands of a few media empires, stagnant and unremarkable works of art are possible. Reproduction continues to be a contested territory of artistic production.

The relationship between the plate, the “matrix” as it is called, and the print finds many resonances in the wide-ranging debate of the copy and the original, especially in the twentieth century. However, while the fragility and ephemerality of this relationship has provoked considerable philosophical reflection and has been noticed as a central feature of printmaking, it has rarely been explored within the medium to any consequence. In one notable essay, Charles Cohan argues that “the matrix acts as a memory of residue and impression, of charging and discharging. It is a structure of faith. It connotes a belief in that which is produced by transfer – not the thing itself, but its imprint.” (7) By taking the print image to be the residue of the encounter with the physical plate, we can explore the philosophical implications of the “event” raised by print practice.

It was Sigmund Freud who proposed the full implications of conceiving the psychic processes as the “residue of an impression” of physical events: there are residues for certain psychic events that the subject cannot process, that they cannot find an adequate way to integrate into the psyche. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud reasons why people would psychically repeat past traumatic experiences; the unconscious residue gets repeated as a new opportunity for the subject to integrate them psychologically. Repetition is therefore the key to uncovering those experiences which were originally repressed and stored in the unconscious. The expression of their repetition is through surrogates or symptoms but the subject is oblivious to their true source. It is the job of the psychoanalyst to decode the events, so that they can be rendered comprehensible.

The process of the psychoanalytical cure is through the relationship of the transference which constructs a situation to reproduce and detect repetitious behaviors which normally go unnoticed. For where the psychoanalyst looks for repetition in the actions of the subject, in words or actions, the materialist historian looks for a “constellation”, a situation that resonates strongly with a previous configuration. That situation in which time seems to stop is the configuration pregnant with tensions. Walter Benjamin’s word for this is the monad: “Thinking involves not only the flow of thoughts, but their arrest as well. Where thinking suddenly stops in a configuration pregnant with tensions, it gives that configuration a shock, by which it crystallizes into a monad. A historical materialist approaches a historical subject only where he encounters it as a monad. In this structure he recognizes the sign of a Messianic cessation of happening, or, put differently, a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past.” (8) The monad is thus the moment of discontinuity with a smooth succession of linear time. Likewise for Donna Haraway, “a breakdown is not a negative situation to be avoided, but a situation of non-obviousness, in which some aspect of the network of tools that we are engaged in using is brought forth to visibility… Breakdown is the moment when denaturalization occurs, when what is taken for granted can no longer be taken for granted precisely because there is a glitch in the system.”(9) The moment of discontinuity is an opportunity to re-examine the situation.

The unconscious is atemporal, existing outside of time. “History” is therefore created retrospectively by the subject in the present. The key is that there can be no return to the original event and the way it really happened because it no longer exists; the effects of the history have to be dealt with in the present. The transference creates a short-circuit between the present and the past that arrests temporal continuity because of the signifier’s synchrony: “It is literally the point of “suspended dialectics”, of pure repetition where historical movement is placed within parentheses.” (10) This corresponds to Walter Benjamin’s view that the meaning of historical events is always made retro-actively and is altered by changes in the symbolic practices of the culture of which they are a part: “To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it "the way it really was" (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger. Historical materialism wishes to retain that image of the past which unexpectedly appears to man singled out by history at a moment of danger. The danger affects both the content of the tradition and its receivers. The same threat hangs over both: that of becoming a tool of the ruling classes. In every era the attempt must be made anew to wrest tradition away from a conformism that is about to overpower it. The Messiah "comes not only as the redeemer, he comes as the subduer of Antichrist. Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.” (11)

Through the process of appropriating the past we have the chance to understand it in a new way and this recognition can change our view of history. The struggle is to contrast the “triumphal procession of the victors exhibited by official historiography” with the histories that will give a more just account of the barbarism necessary in them: “The past has deposed in it images which could be compared to those retained by a photographic plate. Only the future disposes of developers strong enough to make appear the picture with all its details.” (12) With the critical re-examination of history it is possible to learn from our past misconceptions, failures, prejudices and redeem them.

1. Robert Fucci, Rembrandt’s Changing Impressions, Cologne: Walter Koenig, 2006, p. 35-36. 2. Christian Rattemeyer “Drawing Today” in Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing, London: Phaidon, 2013, p. 8. 3. Emma Dexter, “Introduction” in Vitamin D: New Perspectives in Drawing, London: Phaidon, 2005, p. 6. 4. Timothy Van Laar, “Printmaking: Editions as Artworks,” The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Univeristy of Illinois Press, Vol. 14 No. 4, October 1980, p. 99 5. Timothy Van Laar, “Printmaking: Editions as Artworks,” The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Univeristy of Illinois Press, Vol. 14 No. 4, October 1980, p. 101 6. Walter Benjamin, “Eduard Fuchs: Collector and Historian,” New German Critique, No. 5, Spring 1975, p.38 7. Charles Cohan, “The Net of Irrationality: The Variant Martix & the Tyranny of the Edition,” Comptemporary Impressions, Fall 1993, p. 9 8. Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Concept of History, Thesis XVII,” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World 1968, p. 262-263 9. Terry Winogrand and Fernando Flores, “Understanding Computers and Cognition,” quoted in Donna Haraway, How like a Leaf: Simians, Cyborgs, and Women, p. 115 10. Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, London: Verso 1989, p. 157 11. Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Concept of History,” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World 1968, p. 262-263 12. Walter Benjamin, Gesammeltre Schriften, Volume I, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1955, p. 1238.